This is a REALLY LONG POST. I recommend spreading out reading it over a few days. Or, you know, just skim it and look at the pictures. I won’t know the difference. I’m not even sure who all is reading these days. You all look like bars on a graph to me.

It was quite late in the day to be starting my first day into the hundred mile wilderness, given that I only had 7 days worth of food for Copper and me. (Yes, I was carrying half of his food to begin with, in a large bag. He carried in Tupperware, which, since his bowl had gone missing on Mt. Adams, he could eat out of) I needed to make ten miles to the Wilson Valley Lean-To before I slept if I were to stay on schedule. And not staying on schedule was not an option when you the trek ahead means crossing an under-trafficked logging road only every other day. The problem was, the trail doesn’t wait until after the first day to start throwing you in front of things worth taking pictures of.

For instance, right past the warning sign, I already reached the first pond of the wilderness: Spectacle Pond. All the ponds out here are scenic, so I succumbed to my urge to move quickly, and skipped the picture. An hour and two more ponds later, I dropped down a steep hill and landed at Leeman Brook Lean-to, where most of the hikers leaving that day had already gathered, some to snack, some just to chat, and some to have a safety meeting. Among the hikers already there were Counselor, Wonder Boy, and Piper. (The latter two may have been largely responsible for the safety material.)

I set my pack down for a moment, and took Copper’s off. We breaked long enough to eat a handful of Starburst (as I had brought several tubes full for the journey), but resisted the urge to stay longer. The 7.5 miles ahead weren’t going to be nearly as easy as the first 2.5, and there’d be better places to stop for breaks. Counselor bounced shortly after I did, soon enough that Counselor caught me taking pictures on the shore of North Pond just a few minutes after leaving the shelter. He had to stop and admire it as well; it wasn’t a scene to be resisted. We both found ourselves wishing for a canoe. While we mused, Piper and Wonder Boy blew by.

The entire herd of us soon came back together again just 2.5 miles later, to take a break on top of Little Wilson Falls, which the trail is skirts the top lip of. We all walked out onto the rocky ledge around which the water flowed before pouring over the falls, and took off our packs. Most likely, the entire ledge would be flooded during the spring melts, but there were plenty of dry spots for everyone while we were there. I rock-hopped over to the other side of the creek and took some pictures back across of everyone, while Copper stood at the edge of the water wondering whether and how he could come join me.

We all hung out here for quite a while. Most were just sitting and chilling, but I couldn’t help but explore everything. When I felt I’d covered all the ground, some time in the middle of the 4 o’clock hour, I packed up and we moved on. The trail drops immediately along the edge of the ravine formed by the falls, then comes out at a crossing less than half a mile downstream. Little Wilson was, despite the name, just about the deepest ford I had to actually ford in Maine. The stream went around a bend, leaving, for the moment, a dry rocky bed from which one could walk out to a small island. Here there was a small tree, and a rope strung across a narrow gap to the opposite shore. I stopped here to take off my shoes and my ankle braces. Angry Bird showed up at the same time, so I invited him to go first while I put my camp shoes on. He happened to have a spare carabiner, which he could use to hang his trekking poles from the rope to use as a sliding handle. I thought this was a wonderful idea, so I had him hang my poles too. (Did I mention my parents brought a new pair up with them?) I had a slightly harder crossing than he did, since I had to maintain my balance not only under the weight of my pack, but against the weight of Copper pressing into me with the force of the stream. I kept him on the upstream side of me the whole way to keep him from being washed down, though I hoped the Tupperware in his backpack would serve as a lifejacket for him if he managed to slip by before I could grab his handle. It took some effort and care and some leaning on the rope, but we made it without mishap.

We had 3.5 more miles to go and just two hours to dark, and the terrain in Maine is somehow hard to move quickly across, so we did the closest thing to running the next section of trail would allow, not really seeing anything worth stopping to see anyway. Before we knew it we were at Big Wilson stream, another ford, another rope, though this time, much shallower and wider. Since the shelter was only about a half mile further on, and the sun had already set, I decided to just plow right through with my boots on, and let them dry overnight. It’s what the ATC recommends for fords anyway.

I didn’t even stop to get out my headlamp on the other end, hoping to make it to the shelter using only twilight and Copper’s nose to find the trail. We were doing quite well when Angry Bird caught up with me with his headlamp on. On the one hand, as long as he stayed close behind me, he lit the area in front of me as well, but on the other hand, I lost all semblance of night vision, and became utterly dependent on him. Yet nonetheless, I was able to lead him all the way to the shelter, staying just inside his beam of light, with not a word spoken between us, and without having to stop to fish out my light. Boy, was I glad to be there. I was absolutely ready to take off my wet boots and socks and let them air dry. I had fed Copper earlier on the trail, so I ate in the dark and went to bed in the shelter.

The next day the sun rose on a day every bit as gorgeous as the previous. There were a handful of people at the shelter, but I headed out ahead of most of them. My boots were only just barely damp when I put them on and Copper and I hiked out.

It was an easy (for Maine) five miles to the Long Pond Stream Lean-To, where we took a short break and snack that morning. I had been worried about getting my boots wet again fording the Wilber Brook, but it turned out to be easily rock-hoppable, as someone had painstakingly strung rocks that just barely reached the surface across the entire stream (and, at one point, a rotting log). Copper, of course ran back and forth on the edge of the stream until he saw that I wouldn’t be coming back his way, then charged right in, with no qualms about getting his feet wet. The water never came up past his belly.

Shortly thereafter, we were climbing Barren Mountain on our way to the best views we got in the wilderness. We came out onto Barren Ledges alone, and spent quite some time there, as other people came and went. I was unable to resist removing my pack to climb down to the edge of the ledges for the most panoramic views. And Copper followed, as going downhill has always been the easiest bit for him (except for that one time—you know—).

Of course, when it was time to go back up, he decided that down was more his style, and jumped over a ledge to the side, from which there was no easy way back up to the top. I had to climb back down, go over the ledge, and lift him over rocks until he could see the way to climb up.

Before leaving here, I fixed my lunch, because the next shelter was nearly a half a mile downhill from the top of Barren Mountain, and who’s gonna go a mile out of their way to eat lunch?

There’s nothing to see from the top of Barren Mountain, but Fourth Mountain, on the far side of Barren and across some bridges through a mountaintop bog, about five miles past the ledges, gives one quite a distant panorama on a clear day.

Angry Bird caught up to me about this time, and we hiked pretty much together, chatting, all the way to Third Mountain. We talked a minute about the weather, which looked to be about to change. You can tell from the cloud cover that rolled in between the Barren Ledges and Fourth Mountain in the pictures above (over the span of 3.5 hours between 2pm and 5:30pm) that the weather was changing quite quickly. Those clouds were sinking, and by the time I arrived on Third Mountain (to the surprising sight of a half-collapsed fire tower—a framework whose platform and walls were on the ground all around it), it was already sprinkling. The sun was disappearing as well. I let Angry Bird get ahead, as I slowed to enjoy the rapidly disappearing views from the ledges on Monument Cliff, though I didn’t find it noteworthy enough to turn my phone on for.

I caught up to Angry Bird setting up his tent in the col before the summit of Chairback Mountain. I gave him a good night and a good luck before getting out my headlamp and heading off into a dark, stormy night to do the last two miles to Chairback Gap Lean-To.

It was really spooky hiking into that dense fog in the dark, but I had my earphones in and an audiobook going to distract me. (It was the first Ministry of Peculiar Occurrences Book, acquired via Overdrive from the library which gave me a free card back in Waynesboro, PA.) I was already feeling quite miserable by the time I turned around to realize Copper hadn’t followed me. Some lightning was headed our way, and he must have ducked and covered at some point. I had to go back about a half-mile before I found him, so a one-hour trip was stretched to two, and I was absolutely starving.

Counselor, Wonderboy, and Piper were already in the shelter and tucked in when I arrived, having beaten the rain and remained high and dry. There was room at the inn for both Copper and me, so I climbed in and cooked right there on the lean-to’s bunk.

A word about the lean-tos: You’ve heard me referring to the three-walled hiker hovel as a “shelter” for most of this story, and if you’re from where I’m from, a “lean-to” should rightly refer to a makeshift shelter consisting of an array of small branches leaned tent-like up against a low branch of a tree, the cracks stuffed with leaves, yet, nonetheless, all of the MATC’s constructions are named “lean-tos”. In fact, they are constructed fairly similarly from trees found near the site, and in such a fashion as is rarely found outside of Maine. The MATC has even published a book on the subject of how to build their particular breed of shelter. The basic design actually predates the A.T. by quite a bit, invented by the most common residents of Maine’s backwoods in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries: the loggers. Unlike the typical three-walled construction found most places elsewhere, the MATC lean-to has three-and-a-half walls, the half being the approximately four-foot-high “deacon seat” which crosses in front of the shelter. This low wall serves as a convenient seat/table for the occupants, while separating the critters from the gear one might wish to stash behind it. It does not connect directly to the bunk, however. The bunk is typically about the same height as the deacon seat, but is separated from it by about 3 feet of open space, which has been referred to as a “porcupine trap”, due to the unwillingness of most porcupines to leap across it onto the bunk to give the sleeping hikers the night of their lives. Here, for instance, is Chairback Gap Lean-To:

It was even wetter when I got up. The kind of day I’d seen way too many of back in April and May, and hadn’t felt too remorseful about just spending in a tent or shelter, reading and waiting for sun. Waiting in the 100 Mile Wilderness was not an option, though, as I had to be to Abol Bridge in five days, as neither Copper nor I had more than that much food. Of course, I had one opportunity to get a tiny bit of resupply if I could swing it, but I had plenty of other good reasons to be on time: my parents would be worried if I missed my pick-up, and they’d have to pay for an extra day of a vacation that had already gone on a month, and would go on for nearly a week and a half even after my arrival as I finished up Maine. So, after sleeping late (as sleeping when it’s raining is so nice), and taking my sweet time about breakfast and such, I loaded up my stuff, slipped into my Packa, and started my way down the back of Chairback. I wasn’t halfway down by the time the fog had lifted and the rain let up.

Three hours or so later, I arrived at the Katahdin Ironworks Road, one of only five roads that cross the A.T. in the Hundred Mile Wilderness. (By comparison, a randomly selected hundred miles in central Maine has thirteen road crossings. In middle Virginia, an especially wild randomly chosen hundred mile stretch has twenty-four, most of them paved.) Here is where I first found one of the police flyers tacked up requesting information on the whereabouts of Geraldine “Inchworm” Largay, who had disappeared three months earlier, but who is still being searched for even now. The flyer mentioned a number of hikers who had been hiking around her by trail name, presumably because she had signed a shelter register they had signed.

Just beyond this road was the west branch of the Pleasant River, which looked to be nearly impassable without fording. However, at a particularly wide section a thousand yards downstream, I tossed a large rock in a gap, and then managed to rock-hop to within five feet of the rocks lining the opposite side. Fortunately, another hiker, a middle-aged man headed south, had come down that way to try his luck at finding a rock-hoppy path, and tossed a couple of big rocks into the final gap, and so I made it across with dry feet.

The place where we came out onto the bank (for Copper had taken the wet route to follow me after quite a bit of coaxing) was near a makeshift campsite near where the trail climbed up onto the high bank, but I didn’t see it and walked all the way back to the “official” fording site before I realized the way out was back the way I’d come.

It was all uphill from there, but very gentle, though with nothing much to see. It started raining again a couple of hours later, and I still have the inkstains and smudges on my “waterproof” profile map to remember it by. I managed to tune most of it out with the audiobook, but I was still getting restless. I remember constantly wondering why I wasn’t at the shelter yet.

Finally, at the tail end of dusk, I tiptoed across the stream that serves as the water source for Carl Newhall Lean-To to see someone there gathering water. He told me the lean-to was just up the stairs and off to the side. Sure enough, there it was, with clotheslines already strung and wet clothes hung up every which way to dry. Counselor, Piper, and Wonder Boy were all inside, comfortable in their sleeping bags. I got in out of the rain as quickly as could, and hauled Copper in behind me, lifting him bodily over the deacon seat. I’m sure he was as happy as I was to be able to lie down and get dry. There was room for us all in the shelter, though I think we might had trouble fitting many more. Certainly, once I’d hung my own wet things up, some of them from the rafter directly above my sleeping bag, there was no room for anyone else to do so.

I went back alone to grab some water for supper from the stream, and then got out of the rain for good, and cooked right there on the bunk with my sleeping bag stretched out behind me.

I had originally planned to do another two miles that day, over Gulf Hagas Mountain to the Sidney Tappan Campsite, but I don’t regret a bit stopping early (after only ten miles) for the warmth and dryness and company of the lean-to.

The next morning, it had stopped raining, though there was still plenty of cloud cover, and straight out of camp, we were hiking directly up into those clouds. West peak is 800 feet up in half a mile, then, a mile later, 700 more feet in another 0.7 miles. It’s the first of three peaks above 3000 feet in the Wilderness, all to be done in the span of a few hours. Which meant we were in the fog, in the cold wind, and were lucky when we could jump down from a rock into the mud track between the scrubby trees. But the trail started out pretty nice, with a carefully-built rock staircase.

Two miles later, we summited Hay Mountain, dropped down, and started climbing straight up the side of White Cap, the highest peak in the Wilderness, and the last major peak before Baxter Peak on Katahdin, which lay 83 trail miles away. It was probably only half that as the crow flies, but as I said, it was rather cloudy, and I could only see the base of Katahdin in the distance. I could also see some leftover snow/ice hidden under rocks which had never melted, even at this low elevation, and sympathized with its perpetual cold as I ran to get down behind some trees as quickly as possible.

And so, half an hour later and 1200 feet lower, I arrived at Logan Brook Lean-To for lunch. All the other hikers had already arrived, except for Piper, whom I’d passed and stayed ahead of on top of White Cap. She caught up presently. We chatted and had some, and someone suggested just staying there for a while or heading down to the next shelter and stopping, They could do that, as they had given Lakeshore House $50 to bring them a bucket of food to Kokadjo-B Pond Road, just 9 miles away, but I had a plan to make it to White House Landing by the following night, and that meant I had to make 12 more miles that afternoon.

So I turned on the speed and did not turn it off. The only thing that had me bothered was the ford of the East Branch Pleasant River, but it turned out not to be necessary, as there was an easy rock-hop across just a bit upstream. I was seeming to have a lot of luck with not getting my feet wet. I felt bad for the early summer southbounders who sometimes had to wait a day or two (in the middle of the 100 mile!) for a flooded stream to go down, or give up and go back out for more food and try again in drier weather. Rock-hopping would not have been an option if the stream were even slightly higher, and it was a fairly fast-moving stream.

Immediately past this crossing, the climb up Little Boardman Mountain starts. It hardly qualifies for the name, but there is a nice little pond up on its ridge. I hiked by too quickly to enjoy it, but Papa Bear got a good picture in 2004.

Little Boardman is closer to molehill than mountain, but it is higher than anything between it and Katahdin. Unfortunately, the limited view from the top doesn’t happen to be aimed in Katahdin’s direction. We popped over the top of it without stopping.

By the time I reached the foot of the mountain and crossed Kokadjo-B Pond Rd. (successfully resisting the urge to head east and find where the Lakeshore House’s buckets were hidden so I could stash my trash in one, figuring I’d probably be able to dump a few things at White House Landing if I made it there), it was dusk. When I saw a fire and a lot of tents down by Crawford Pond, I turned aside to check it out.

Piper and Wonder Boy were there, but appeared to have their tents set up and were already heading to bed. The other group of four was standing around the fire drinking and having a grand old time. I don’t remember all their trail names, as this was the only time I ever saw them, but they introduced themselves as Team Caboose, the group with the goal of being the last ones to climb Katahdin in 2013. They were doing a good job of it as well, because they said they’d been there all down, and in fact, had gotten a ride in on Kokadjo-B Pond Rd after doing a mere mile the day before, offering the rain as their excuse. They certainly seemed to be going nowhere fast, and had no apparent deadline for getting out of the wilderness. They invited to spend the night there in the doldrums with them, but I informed them that I had a date with a cheeseburger or three the following night (and besides which I’d eschewed my tent to make more room for food), pulled out my headlamp and hiked on. Copper, who had already accepted their invitation and laid down at their feet, only stood up to go when I was halfway back to the trail.

Just a bit past here, the trail took a sudden turn to the right, away from the pond. It joined an old roadbed, wide and nearly level. Right down the middle of it ran dozens upon dozens of intermittent bog bridges, many of them rotting and falling apart.

I thought it would be a quick and easy trip if the roadbed held out, as the profile showed nothing but two and half miles ever so slightly downhill to Cooper Brook Lean-To. But after 16 miles, I was footsore, and I was hiking in the dark, and I was finding it harder every moment to forget myself and listen to the audiobook. Especially since the roadbed didn’t hold out. Somewhere, the trail just turned off in the woods, and become a twisty root-filled rut with trees pressing in close beside. I could still see the road over there, muddier, and better cleared from four-wheeler traffic or something. There were several enormous mud puddles filling the trail along the way, and at one point an entire fir tree completely blocking the trail: no way over or under. I had to go bushwhacking just to get around it. Then there was the place where the trail just went right into the middle of a small boggy stream, with the only ways up onto the back involving backtracking and climbing on downed trees or slip-and-sliding through a mud pit. I remember stopping to fill a water bottle at one of these streams running across the trail, because it seemed clean enough, and because I didn’t want to die of thirst if that two and a half miles of trail just happened to go on forever.

I have no idea what time it was when I finally rolled down the hill into the lean-to, nor do I quite remember the trail name of the only other occupant, who was, of course, fast asleep. I did my little routine of inflating my pad outside the tent so as to make less noise and shine less light, cooked and ate silently at the picnic table, loaded myself and Copper inside with as little sound as possible, and got rapidly to sleep. I don’t even recall speaking to the other occupant. Maybe I was alone and am just misremembering the whole thing.

The next day’s goal was simple: make it to White House Landing before sundown. I had only 14 miles left thanks to my late night, and the trail was not particularly difficult. So, I got up and got ready as early as I could wake up, though the other guy still managed to leave before me. I got water out of the brook, loaded up my pack, and headed back up the hill to the trail.

It was essentially a level trail, winding around the edges of pond after pond. I have little flashes of memory of this section, for instance the Antlers Campsite on the shore of Jo-Mary Lake. I moved through it so quickly I didn’t even stop to check out the two-seater privy “Fort Relief”. (Mainers have a curious habit of building monumental privies and giving them witty names, but more on that later.) Near here is where the trail turns northwest, perpendicular to its previous direct-to-Katahdin route to avoid a cluster of very large well-used lakes and the streams that feed and connect them, and continues that direction for the next 21 miles.

The only real work that day was to climb a tiny hill called Potaywadjo Ridge. After hours of walking on nearly level trail, it seemed like quite the task, but that was probably just my urgent desire to eat lunch after hours of nonstop walking calling. My salvation lay at the foot of the hill: Potaywadjo Spring Lean-to. Copper was more than happy to flop down inside while I fixed a snack, something sweet and filling, probably involving Starburst and Special K bars and peanut butter. I didn’t really care what I ate; I was just happy to be off my feet for a spell. I spent a long while just reading the logs, and I’m fairly sure this is where I found this gem:

You’ve got to know when to ford ’em

Know when to avoid ’em

Know when to walk right through

And know when to runYou never camp on the near side

When it’s looking like a rainstorm

There’ll be time enough for camping

When the crossing’s done.

I left Copper in the shelter when I went down to Potaywadjo Spring to check it out. I had had no idea until I read the shelter logs that it would be so big. It’s a big sandy bowl at least ten feet across, with water seeping up into it from who knows where. The bog bridges go across its outflow and all the way up into the spring, where they can get a little slippery. I collected some water, then went back to get Copper and my pack, so I could lead him down there to get a drink himself. Of course, I had to keep him out of the spring for sanitary reasons, though I wondered if the water was even safe to drink to begin with. I had to expect every animal in the surrounding area watered there when it could. I treated the water I got there.

I wasn’t in too much of a hurry at this point, since it was only three miles to Mahar Tote Road, and I only needed to get there before 5, when they closed up shop for the night. I felt so comfortable about making my deadline that I figured I could take a few minutes to head off trail when I reached the south end of Pemadumcook Lake to go see what Katahdin looked like from a distance on a clear day. There’s a beach, and a pile of driftwood, and some rocks to walk out about into the lake. And there in the distance, like a Yes lyric, was the mountain.

I arrived at Mahar Tote Rd around 4 pm and turned to head down it. It’s a muddy old dirt road for moving boats between lakes, hedged in on both sides by tall firs, leaving little room to skirt the deepest mud. When it arrives at the lake, there’s a huge arrow sign stuck to (or leaned against?) a tree, and I felt the arrow was talking to me specifically. It said “go back into the woods here!” So I did, and soon found a winding narrow track, barely trodden down, far from cleared, rarely maintained, but zealously blazed with large blue patches of spray paint across the face of every rock and tree that comes within two feet of the trail. It was twice as difficult to navigate as any of the trail I’d trod all day long. To be honest, I hadn’t read carefully, and I hadn’t realized that the trail to the White House Landing dock was almost a mile long by itself. I really didn’t feel like walking much any more, and I was certainly not willing to stand any more once I reached the dock at the end.

It’s directly across a wide cove from the house; it’s easy to see on the far bank. Hanging from a tree next to the dock is an airhorn and a sign, instructing one to give the horn one short blast and to wait however long it took to get a pick up. I thought I might give it a slightly longer toot, but it was so loud that I let up as soon as it hit my eardrums. Copper and I walked out onto the dock and laid down in the middle of it to wait. I recommend this flickr album to see what the airhorn and the hostel are like. And here’s a photo and a silent film:

So we waited and we waited, and half an hour went by, and dusk was starting to get near. So I stood up and peered toward the house. Eventually a figure came down to the dock, got in a boat and started it. (The reason the hostel is accessible only by boat is that it could be walked to by following the trail past the end of Lake Pemadumcook, fording the Tumbledown Dick Stream, and then hiking east for a mile and a half through a mix of forest and private property, but very few hikers would be willing to go to that much trouble. Even the mile of trail that I did have to do would have been excessive to me if I hadn’t planned on spending the night.

Now I know people say that the owners aren’t very friendly. People were telling me that all throughout the wilderness, and you can see people saying something similar here, but I thought that couldn’t be. How can you run a hiker hostel, yet be unfriendly to hikers?

But it turns out that Bill is just sort of a grump who’s fed up with the whole hostel scene. One of the first things he said upon picking me up (after apologizing for not having seen me out on the dock sooner because I blended in with it when I was sitting down, for which I held no resentment anyway, as I find sitting beside a lake on a clear autumn day to be quite restful) was how obnoxious it was to be a slave to an airhorn, running back and forth with ungrateful thru-hikers who were just coming to pick up some extra food and not even spend the night. Based on first impressions, it seemed all the rumors were right, but I was going to spend the night, and I hoped, enough money to make it worth their while to have me. I know one guy isn’t going to change someone’s mind about thru-hikers who’s had a decade of experience with them, and that it wouldn’t matter anyway, since he told me it was going to be his last year the business, but I was going to be my most mannerly anyway. It’s hard not to react that way when someone puts you on the defensive with their first words to you.

Based only on their greetings, Linda seemed like Bill’s foil. It was readily apparent they were both very hard-working, trying to operate a hostel just the two of them, but Linda had “accommodation” in every note of every word she said to me. She showed me to the lodge, and a sink. I washed my hand, took off my boots, left my pack on the porch and went inside for supper.

I ordered four cheeseburgers. One for supper, one for Copper, and two for the road. They were enormous and amazing, but they could taste like anything and still be the best food available anywhere in the Hundred Mile Wilderness.

Linda showed me the bunk room and the privy and the shower, gave me a towel, and left for the night. Believe me, I took advantage of every amenity they offered. One amenity they did not offer was electricity. They had some in the main house they lived in for their own computers and devices, but it came from a generator and they didn’t want to run it all the time.

In fact, everything there ran on gas. The lights in the lodge and the bunk house and the privy were gas (and I was instructed not to mess with the dials, on account of the possibility of killing the flame without killing the gas, resulting in a dangerous leak), the giant tanks of water on platforms above the showers were heated with gas, and all of the cooking equipment in the lodge ran on gas. I guess it’s just not sunny or windy enough in the Maine wilderness for alternative energy sources.

There was a shelf stocked with books in the bunk room, and I grabbed a vampire novel to take to the privy before my shower. It was utter crap, and after part of the first chapter, I couldn’t bear to read any more of it. There was also a non-fiction book there about hashing, a sport which I’d never heard of, but read about with great interest. I can’t seem to Google up the book I was reading, though you can get a reasonable summary on Wikipedia.

Eventually, well after dark, I spread out my bag on a bunk under the northwest-facing window, killed the lights, and pulled Copper up into the bed beside me. He didn’t move or wake me up all night until the sun woke me up for breakfast.

Breakfast was at seven and a “Don’t be late!” sort of affair, even though I was the only one there. I was so anxious about it that I woke up at 5 AM and turned my phone on just to check the time, then fell back asleep. But the second time I woke up, I got out of the bag immediately, put Copper on the floor, mixed myself my customary protein shake (which was a rarely broken breakfast ritual that I never became tired of, and I needed to use it up to lighten my load anyway), threw on some shoes and headed straight for the lodge.

Linda had the coffee ready plus a small glass of orange juice, and made as many pancakes with jelly as I thought I could eat, and scrambled eggs on the side.

After that, I bought some m&m’s from their small resupply store, hit up the privy, packed up the rest of my stuff, and brought my pack to the porch of the lodge. Bill and Linda had some chores to do, and Bill couldn’t give me a boat ride back to the trail for a few minutes, so I took Copper for a walk to get a few pictures of the place.

This last picture is the racks of drying driftwood Bill has collected from the lake. While he’s not too keen on hiker hostels any more, he’s very into driftwood, and becomes a very friendly and likable guy once you ask him about it. Here’s the deal: lakes in Maine are just filled with driftwood, and it belongs to whomever wants to pull it out of the water. In Florida, on the other hand, where the Ware summer home is, the stuff is extremely valuable for use in furniture and art, worth up to fifty thousand dollars for a small truck full. Bill already had a buyer, once he managed to get the stuff down there. They had even put together a piece similar to the following (from Etsy) as a demonstration.

Although their version included an acorn as well (because every family has a nut).

Anyway, Copper decided to leave them a present, so Bill showed me where the shovels were in the toolshed, and I tossed it all into a bush down the shore a bit. Once the shovel was put up again, it was 8:30am: time to get back on the trail. Copper and I got in the boat and sat up in the bow, in front of the cockpit. I put on my fleece to brace myself against the cold wet morning air over the lake as we sped through. It was barely enough, and I was quite chilled by the time Bill drove up onto a large sheet of plywood laid across the bank. I grabbed my pack and jumped off the bow, and Copper jumped down behind me. With a single word of farewell, Bill backed up and headed home. I put my earphones in and looked around.

He’d left me back on Mahar Tote Road right where it first came alongside the lake (not far from the arrow directing traffic into the woods). I still had to navigate the mud bogs, but I was within a quarter mile of the trail. I was worried I’d have to ford the Tumbledown Dick Stream as soon as I got back on the trail, but it was such a tiny little thing, I hardly even noticed.

The trail starting by following the river that connects Nahmakanta Lake to Pemadumcook Lake (presumably called Nahmakanta Stream), staying on the south bank. Somewhere halfway between the Tumbledown Dick Stream crossing and the crossing of another unidentified stream, it passes by the Nahmakanta Stream campsite, which is near the bank of that river-like body. Further up, after the shallow crossing of the unnamed stream, it climbs a hill via a metal staircase, which was dragged by who knows whom into the woods to make it easier to climb a mole hill. Its very presence called into the question the entire experience of a Hundred Mile So-Called-Wilderness.

Next, the trail crosses a gravel road and then follows the edge of the Nahmakanta Lake, near which one can find a number of canoes chained to trees. Canoeing seems to be one of the most popular activity among Northern Maine locals. At one point, the trail just randomly comes out onto a sandy beach before diving back into the woods again. Soon, Copper and I crossed the Prentiss Brook, which feeds Nahmakanta Lake. A mile-and-a-half later, I was super-excited to reach Wadleigh Stream Lean-To, as it meant I could finally stop and break into that cheeseburger that Copper had been carrying for me. Of course I gave him a few bites of beef as a reward. I washed it down with a pack of peanut M&Ms.

After leaving here, it was time to head up a little 2000-foot peak called Nesuntabunt Mountain, which despite its tiny size, still manages to stand high enough above the surrounding landscape that there is a good view of Katahdin from near the top via a short side trail. Katahdin was 16 miles away from this spot as the crow flies, but the distance for hikers who can’t walk on water is another 31 trail miles to the base of the mountain.

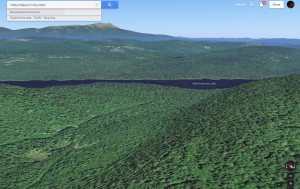

Google Earth’s rendition of the back side of Nesuntabunt Mountain, Lake Nahmakanta, and Mt. Katahdin

Somewhere down the backside of this mountain, I came near a slot canyon called Pollywog Gorge, and spied a trail that went straight down to a rock, an angel’s rest, standing above the canyon wall. I sat here for a while and drank some water and ate a snack and just stared at the view. Then, before I left, I picked up some random garbage the last visitors had left there and put it in my pocket. Minutes later, just over the next hill, I was walking around a pond again (probably Crescent Pond), amusing myself with the thought of trying out one of the more poorly secured canoes. Having never gotten all that far above the level of the lakes, it didn’t take but an instant to be padding their shores again.

Down in the valley behind Nesuntabunt, the trail joins a well-maintained gravel road just long enough to cross the Pollywog Stream on a brand-spanking-new wood plank bridge. Not an unwelcome mode of crossing to be sure, but yet another shock to the illusion of wilderness.

2.5 miles later, I had arrived on the banks of the Rainbow Stream, where stands the appropriately-named Rainbow Stream Lean-To. Even though it had been a relatively easy 15.5 mile day, and we arrived at dusk (sunset was about 6 pm this far north and late in the year), Copper and I were both glad to see it.

Another hiker had gotten a fire going there and then attempted to sleep, butgot out of bed to chat with me while I ate dinner at the picnic table. He said he hadn’t come in too much earlier than me, and was unable to get to sleep anyway. He told me about himself too, but it’s been so long. I think he was from Texas. He was duly jealous of my cheeseburger. I’m pretty sure he was stoned. He told me there was a falls and swimming hole just up from the shelter and the water was good in the stream. I went to bed as soon as I was done eating. Copper beat me to it by half an hour.

Rainbow Stream Lean-To is one of the last traditional lean-tos in all of Maine. Whereas most of them now have planks for the bunk, once upon a time, they all had “baseball bat floors”, which means they were floored by small, smoothed trees about 4″ in diameter. According to David Field, the “old hiker way,” practiced up through 1960s, required the first hiker to reach each shelter during each hiking season to cut the small branches of fir trees and pile them in the shelter to build a mattress upon which one could lay one’s sleeping bag directly and sleep directly. Then, as the mattress got compacted throughout the season, hikers would build it up with fresh branches. Comfortable AND fresh-smelling!

Unfortunately, with the much higher volume of hikers the hiking trails and lean-tos have seen in the last couple of decades, denuding trees to make a bed is no longer sustainable. Nowadays, most hikers carry some sort of mat or pad to sleep on, which serves just as well to cushion sleeping hiker’s backs from the bulging edges of those “baseball bats!” Copper normally doesn’t use a pad, but for this night’s stay only, I let him share mine.

The next morning, after using up the last of my protein shake powder, visiting the privy, washing my pot, and filling up my water bag in the brook, Copper and I set out on the final leg of the Hundred Mile Wilderness. I was in no hurry, as I’d promised to come out of the woods around 4pm that day, and I had less than 15 miles to go. Starting by eight and going the previous day’s speed would do just fine. I left the Texan there at the shelter, still taking his time. I don’t even remember whether he’d planned to hike that day, or which direction he was headed. Probably south.

The trail picks up on the far side of the Rainbow Stream, so the first item of the day was to trot across the pair of denuded trees that served as bridge. Copper started to follow, then decided he liked walking in the stream beside it better. When the stream got too deep to walk, he gave up and went to the bank. Eventually, I coaxed him out onto the logs, and he made it across the human way with no problems.

There is very little to report about the next eight miles. The trail spends the follows the Rainbow Stream upstream to Rainbow Lake, follows its south shore to its eastern influx, skirts around Beaver Pond, crosses the little stream that feeds both lakes, then sets out on a direct route toward Abol Bridge, remaining utterly flat for another four miles. Yes, it’s 8 miles of almost perfectly flat trail. This doesn’t mean I could get the kind of speed I could get in the Shenandoahs, because there are just as many roots to avoid and far more bog bridges than usual, but it’s certainly one of the easiest sections of trail I saw in Maine. In addition to the sameness of the trail, I had finished the last audiobook I’d downloaded at Lakeshore House and couldn’t find a radio station, so I had started listening to the same audiobook over again. Despite the near-constant view of the lake, it’s safe to say this little piece of trail quite bored me. I found myself counting down the miles to Rainbow Ledges, which was the only interesting feature on the profile map for that day’s hike.

I stopped for a few minutes about halfway there at Rainbow Lake Campsite, which is situated directly on the lake’s shore, sat next to the water and stared. With the cool autumn weather, the clear, lightly breezy day, the sun slanting through the trees dappling the pinestraw with diffusion patterns, and the birds twittering in the trees, it was a perfect moment. I listened to a pair of loons call to each other while I ate up the last of my special K bars.

Five identical miles later, I finally reached the Rainbow Ledges! Believe it or not, for once I was excited to be going uphill. Why? Because maybe there was a view at the top? Nope. Just a lot of sunshine and sweat. It was more like a bulging exposed rock hump than a ledge. Actually, it was kind of like Lowe’s Bald Spot, but with less scenery. I say a couple here hiking together in the opposite direction! They were the only hikers I’d seen since I left that morning. Exciting, right?

At the base of the ledge was the Hurd Brook Lean-To—the last lean-to in the Hundred Mile Wilderness! I didn’t stay here for long. I think there may have been one hiker setting up next to the shelter already, preferring to stay there for free rather than pay at Abol Bridge or hike another 13 miles in the dark to The Birches Lean-To in Baxter Park. The whole area in front of the lean-to looked more like a bog than a stream. The stream came around the bases of trees, splitting and resplitting to form an island chain spanned by log bridges or near enough to one another to hop across. In places, it pooled and became stagnant and dirty. No way I was going to fill up on water there. Copper had no qualms about it whatsoever, and was never the worse for wear for it.

But the end of the wilderness and my rendezvous was only three miles away and I had only an hour to get there according to my declared schedule. I found myself practically talking myself up to top speed through this last section, counting every step, wondering over and over again “Where’s the bog bridge? Where’s the bog bridge? Where’s the bog bridge?” The profile said there was a bog bridge half a mile from the exit, and after an hour (perhaps, as I never stopped to check the time), I felt like I should have already reached it. When I got to it, I was so excited I actually started trying to get Copper psyched up about how close we were. I knew my speed was even harder on him than it was on me, and I was getting pretty weary myself. The bog bridge went on continuously for maybe a quarter mile, and then I could start seeing and hearing the signs of civilization. The Golden Road is not the most heavily traveled roads; after all, the logging companies built it themselves and maintained it for their own use. However, it’s probably the most happening logging road in Maine, and I could hear a car or two long before I could see it.

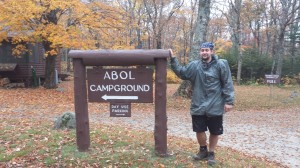

We finally reached the road about 5 pm, and there was my parents’ rental right around the corner. But I couldn’t have them pick me up there. There was a 0.3 mile section between the Hundred Mile Wilderness northern terminus and the restaurant at Abol Bridge Campground, where I expected to be picked up the following day. So, we hugged, got exit photos, and then I said “I’ll meet you on the other side of the bridge.” Daddy said “That’s stupid. I can drive you over there.” Mama said “I’ll walk with you and get pictures. Copper said “Nah, I’m good,” and got in the truck to ride across.

Once I arrived at the restaurant/convenience store, I insisted on going in, even in my state of filth, to get an ice cream cone to celebrate. Once the hardest decision of the day (what flavor?) had been made, I ate ice cream while I changed into clean clothes and stuffed the reeking ones in a trash bag with my pack and boots. My parents were much better prepared for the stench this time.

Copper rode across my lap for more than half an hour to Millinocket and the Katahdin Cabins, where I finally got to get a shower. Then, we went over to the kitchen cabin and cooked some steak and potatoes for supper. Sure it wasn’t steakhouse quality, and sure I wolfed it down as fast as I always do, but to a starving hiker, any real food is heaven. I think I might have even had a beer.

I hit the hay as soon as I we got the kitchen cleaned up and Copper inside the cabin. I couldn’t stay up and celebrate my triumphant return to civilization, as there was still a mountain to climb, and there’s no way to get on the mountain unless there is parking available at the trailhead you want, and there’s no way to guarantee that except to arrive there at the crack of dawn. Copper climbed into bed with me, and that’s how we spent the night.

Mama got up with me at 5 AM the next morning to go over to the kitchen cabin to make some quick grits to run on. I put together my slackpack in the truck on the way back to the park. We arrived two minutes before 7am, and already my preferred trail up was full up for the day. I elected to climb the Abol Trail, the shortest route to the top, instead.

The clouds in the sky didn’t exactly indicate I would be having any wonderful views, but I still had hopes it would clear up. For the moment, I changed into my raincoat and fleece and long pants, signed in at the ranger station, and got my slackpack on. Mama helped me rig a bungee as a strap to keep my collapsed trekking poles on my back and out of the way tucked into my hip belt. I would need my hands quite a lot for the climb up, you see. It didn’t work great, but it worked well enough. I hugged Mama a quick goodbye and told her what time I expected to be back at Abol Bridge, then set out up the road.

I set off just as a young couple, one of whom had never climbed before, was starting. They were both in quite good shape, and I pumped it to keep up with them up the road to the trailhead proper. However, they didn’t have mountain legs on them, because I stayed right on their tails once the trail got steep, and they were stopping to adjust within minutes.

Climbing Katahdin is an interesting thing for someone who’s already walked a couple thousand miles. It’s absolutely filled with people who have no idea what they’re getting themselves into or whether they can handle it. My dad likes to tell a story about how we were passed by a group of thru-hikers the first time we climbed Katahdin, who were moving so fast it didn’t seem like they even knew they were climbing a mountain. This time, I was the thru-hiker, and I was passing people as inexperienced as my dad and I were back then.

Right off the bat, I passed a small group going downhill, who’d climbed in the dark to try to see sunrise, and were treated to a view of “nothing but fog.” Not very promising. Soon, I was passing a group of boy scouts picking their way carefully up the rock face, trying not to slide down in the showers of loose rock that were everywhere underfoot. They were chased several hundred feet back by the obligatory “fat one” who looked like he was barely making it, poor thing.

I passed every single person going the same direction as me, with a smile and a friendly word of encouragement to everyone, and maybe a pointer about the easiest path up. At one point, just shy of the table lands, I came to a place where it wasn’t clear how to traverse from one blaze to the next one up. It was bodily hauling one’s self over giant boulders everywhere I could see from where I stayed, which happened to be directly behind a group of three younger, stronger, but inexperienced hikers, who were picking their way up, as yet unwilling to lay it all out and throw themselves up the mountain. So I passed them, pulled myself up three feet onto a ledge, saw no way forward from there, threw my leg and arm across a large boulder to my left, and found not a single handhold. Smooth as an uncut diamond. So I put both hands on my side of the boulder and grabbed a lip, and used it to lever myself around the rock like a break dancer or something until I found a foothold on the other side. From there the way up was easy and obvious.

Ten feet later, one of the group stuck below the ledge turned to another and said “Did anyone see how he did that?” I was on too much of a speedy mountain-climbing high to go back and advise they try to find a different route. Just because it’s theoretically possible doesn’t mean it’s a good idea. I don’t think what I did would work for anyone under six feet. Or even for anyone who didn’t feel like they were moonwalking any time they were hiking without a 30 pound pack on their back.

A moment later I was on the table lands, and it was just as I remembered it, except there was a rope routing people away from a too-heavily-trafficked section. I hopped from rock to rock, until I was nearer the AT, looked around, and saw no other hikers there. So I peed right there beside the trail. You know, ’cause I had to pee, not because I wanted to demonstrate my dominance over the mountain or anything. (And don’t worry, I didn’t pee in the Thoreau Spring, duh.)

I passed only handful of people crossing the table lands to the staircase up to Baxter Peak. There were only three or four people next to the peak itself. Apparently, I’d put myself ahead of almost everyone else climbing that morning. I didn’t have to wait long to get my obligatory summit shot, which you’ve already seen here:

So I sat down with some Army guy, who was apparently associated with one of the Boy Scouts, and had a snack. I also had a good cellphone signal, so I sent my mom a text saying I’d summited and I’d be back at Abol Bridge well on time. It was about 10:30am. It took just about two hours to reach the top.

I felt like I had all the time in the world on my hands, so since I wasn’t able to climb the Helon Taylor Trail like I’d wanted and do the whole Knife Edge ridgeline, I decided I’d just go out and back on it from the summit. I stashed my pack and poles near the beginning of it, and went out hopping along, jumping from boulder to boulder, feeling like a speck teetering on the edge of oblivion, yet comfortably walled in by the fog. There wasn’t much to see out there, being totally socked in, so I got bored after about a couple thousand feet and turned back.

Here’s what I saw:

Here’s what I missed out on:

When I got back to the peak, some of the people that I had passed on the way up were there, having finally made it nearly an hour later. Although I stayed a few minutes hoping the sun, visible through the fog, would burn off the clouds, the few blue spots of sky I saw were ephemeral and only served to get my hopes up needlessly. I was done, and ready to go back down. I got back down to the table lands and there I passed Counselor. He’d stayed at The Birches Lean-To the night before, and had set out up the Hunt Trail after he woke up, leaving his stuff there in the lean-to. I talked to him for a few minutes, and informed him that if he didn’t feel like climbing the 6 miles back down the Hunt Trail, the Abol Trail would take much less time to descend, and he could hitch a ride back to the Katahdin Stream Campground and his pack from the Abol parking lot. Then, I left him to head up to the peak and went on down.

Right next to the edge where the table lands end on the Hunt Trail, I found a large group of folks just sitting there, chilling out (as there’s no other way to sit in the fog and wind above treeline on Katahdin) after their climb up. It was Team Caboose! They weren’t the last ones after all.

Just a little bit down the bouldering climb down near the top of the Hunt Trail, a group of college kids caught up to me, and one of them was so nimble, he moved down the rocks even quicker than me, like one might jump on a trampoline without regard to safety. I started chatting with them, allowed them to pass near the first rebar ladder, and kept on their tail most of the way down. They were taking a geology field study class, where each day they visited a new location, hiking around and checking out the rock formations and discussing their history and formation. The top of Katahdin seems like an excellent place to study rocks. I started asking them questions, like why some of the rocks I’d seen crossing the rivers and a lot in the very trail we were walking were green. Without losing speed, they gave very complicated answers that didn’t inform me much at all. I rolled my ankle trying to keep up. Their main advantage was that, not having walked all the way through the Whites already, they still had functioning knees.

At some point below treeline, when we were holding on to trees to keep from sliding too fast or launching ourselves too far off the ledges, I had to point out to them that one of their number was no longer with us. Apparently, he hadn’t kept up in our headlong tumble down the mountain. So, most of them stopped to let him catch up, except for one student, who’d stayed up ahead the whole time keeping up an intent conversation with the class’s young, yet still flannel-bedecked professor. So I stayed just behind those two listening in until they, too, stopped beside the waterfall to wait, still continuing their conversation. I learned a lot about where they would be headed the next day, but little about geology, I’m afraid.

Just below the Katahdin Stream Falls is the last privy on the Appalachian Trail. It’s accompanied by a warning that there are no bathrooms on top of the mountain. (Down at the trailhead are information boards that detail the preferred procedure for “emergencies” on the mountain: rock-hop until you get far enough from the trail that no one can see you, then go on top of a rock, not on the sensitive vegetation.) The fact that such a fact needs to be stressed is a further sign of the popularity of Katahdin as a hiking destination for the experienced and inexperienced alike.

Down at the trailhead, in the Katahdin Stream Campground, is a row of picnic tables, where I stopped and pulled out everything that I’d been carrying with me. The main treat I’d been carrying was a bottle (can?) of root beer, which I promptly drank sitting right there at the table. The proper way to celebrate climbing Katahdin is to wait until you’ve made it down again.

After eating and visiting the bathroom, I walked around to the Birches Lean-To to see what it was about and find out who was home. Piper and Wonder Boy had just arrived in Baxter, and were planning to summit the following morning, or something along those lines. I wished them well and headed out toward the road.

This is when most people would end a day hike on Katahdin. We went up, we went down, what’s left to do? Well, what’s left is the ten miles of trail between Abol Bridge and Katahdin Stream Campground. It was such a short, easy section, it wouldn’t have been worth saving for another day. I’d only been like 9 miles, so I was still relatively fresh. Plus, I had just eaten. So I walked down to the entrance, hooked a right onto main road, and walked until I realized the trail didn’t go that way any more. I found where it re-entered the woods much nearer to the campground entrance, signing the register as I went in.

Within minutes of entering the woods, I was walking around ponds again. It looks like the end of the Hundred Mile Wilderness, but there’s a lot more people. Each pond seems to have a primitive campground associated with it, and every spot in every campground is booked solid right up until the day the park closes. There are people out in small boats and canoes on some of the ponds fly-fishing, or just walking out into them in waders. From one end of Daicey Pond, I could hear children playing along the bank in the campsite at the opposite end. Down at that end is a parking lot, so it’s fairly easy to get your gear close to your campsite without carrying it all on your back.

In fact, the trail comes right through the Daicey Pond parking lot. There’s a register coming out into the parking lot, and another going back in. I signed both. In the latter, I signed after Six and Dangerpants, who had written 2pm on the register. It was 4pm. I was disappointed that I had come so close to catching them, and figured I had no chance of seeing them that evening, but I caught up to them just five minutes down the trail. It seemed they had just put down the wrong time, or they had signed, and then taken a very long break before heading on. My guess that gives them the largest benefit of the doubt was that they wanted the park rangers to think they’d come out the other side at Abol Bridge and wouldn’t go look for them stealth camping in the woods. Getting caught camping outside of an official campsite in Baxter is costs a couple hundred dollars, your gear, and a free ride outside the park boundaries. This is all according to the strict regulations under which Gov. Percival Baxter deeded the land to the state, and befits its great popularity and high traffic.

As a matter of fact, when I found them, Dangerpants and Six were hunting a good place to turn off trail and set up a stealth camp. So I walked with them as far as Little Niagara Falls, talking about what they’d done in the last week. What they’d done was get a ride to Millinocket, then climbed Katahdin on a sunny day with a lot of the folks they’d been hiking with since Connecticut. They still had the Hundred Mile Wilderness ahead of them, and the section between Hanover and Mt. Moosilauke. All the days I’d spend wondering if I could catch up to them, wondering how they got so far ahead, were vindicated on this day, when, passing them, I officially had exactly as much of the Northeast left to do as they did. I just did it in a different order than they did.

We went down to the edge of the falls together to get a good selfie and, when the hour seemed late enough—4:30pm with dusk already on its way—I had bade them adieu for the last time in Maine.

I still had seven miles to go by 9pm, so I set off at my rapid pace (also known as the no-pack gazelle moonwalk traipse). I needn’t have been so worried, though, as it was all ridiculously easy. There was literally one uphill section that lasted all of twenty yards. After that, it was all downhill or perfectly level. Just walking along the edges of rivers, over small bridges, on leveled embankments. I was within a mile of the trailhead before it got too dark to see.

I rolled up to the signpost at the end (beginning) of Baxter State Park, and opened the box to see who’d been there, since all through hikers have to register coming into the park if they are planning to stay (for free for at most 2 nights) at the Birches. I took some time to copy down a number of names of hikers I knew on some scrap of paper I had with me, so that I could look them up on facebook later. There was no place to sign out of the park, so I walked on back to the Abol Bridge restaurant.

There were a number of other thru-hikers here, probably nice folks but most of them not my type. These included Trail Wreck, Swagger, Future, and Pundit. And most unexpectedly, G, whom I’d last seen at Chet’s during my second stay there a month before. They hardly seemed interested in socializing with anyone else. They had some crazy snacks, plus a bunch of beers and Red Bulls, and were talking up this crazy plan of night-hiking all night into the park (since they couldn’t afford to stay there and, having found out from a ranger parked nearby about the fine for stealth-camping, couldn’t camp inside) and summiting as soon as they arrived in the morning.

I went inside to get a good hot meal. It was getting nigh on towards closing time, and the prices were as high as you’d expect for the middle of the Maine backwoods. I got a plate of poutine with bacon bits, which exactly exhausted the cash I had with me. (Cards were not accepted.) I didn’t even have enough left to leave a tip. I feel a bit bad about that.

Back outside, I started asking around to see about the possibility of getting cell service. I’d heard that there was a hill a half-mile down the road, and I was trying to find someone with a charged cellphone and a ride to get me down there. Or one of each from two people.

The group of kids getting ready to go in the woods had just come out of the 100-Mile Wilderness to find the pickup truck Future had left there had had a window smashed out and over $2000 of choice hiking gear stolen, right there in the convenience store parking lot. I asked Future about the possibility of carrying me out to the calling hill, but none of them had any interest or regard in me. He flat refused.

Eventually, an older couple came up to give out some extra twizzlers and snickers for magic, and I found out they were Angry Bird’s parents, and had been waiting to pick him up all evening. They offered to let me borrow their cellphone to call Mama, and drive me to a place where I could get a signal. They first tried the trailhead, but nothing there. The only place really was that one little hill a half-mile down.

I managed to get the call in, and Mama said they’d come a bit early to get me. I’d finished the hike some two hours before I said I would, and they were going to end up picking me up an hour early. Angry Bird’s parents also finally got a text from him saying he’d been having some foot problems again, and had decided to stop at the last shelter from the road, and would be out early the following morning. Which meant they’d driven 50 miles to Abol Bridge and back for nothing, and would have to do it again. I thanked them profusely as they dropped me off at the restaurant with more Snickers. I sat with my back to the wall just chatting quietly with the other hikers while I waited, and they still hadn’t made up their minds to leave even as my parents arrived to pick me up and take me back to the cabins, where we had a similar night to the previous, but without the fancy dinner. Mostly I was wrecked, and went to bed as soon as I finished my shower.

We got up early again the next morning. We loaded up and headed out of Millinocket by 7am, and drove the hour and a half to Monson, where I was immediately dropped off again. I had spent the last few days in the 100 Mile Wilderness putting together a day-by-day plan to get through the part of Maine I had skipped in just 9 days. I relayed this plan to Mama as we drove, and as soon as we unloaded at the Monson trailhead, I was ready to put it in action. Copper wouldn’t be going with me: it would be too fast and hard for him. I’d be doing just three nights in the woods (though plans changing would make that four), and would be slack-packing as much as possible for speed, and light-weighting the rest. I would see only a handful of thru-hikers on the way, and those unsure of how their hike would end. Mostly I would be alone. But there was no other hike possible anymore. It was time to get it done.

just wanted you to know …. I am still reading!!! 🙂

I am going to be sad when this hike is over…..I have loved reading this blog. Even though I talked to you throughout the hike, the details make it come to life. Glad you are still taking the time for details.