165 miles is all I had left to go. 10 days is all I had left to do it. Not only had I committed by giving the okay for a day to have people join me on the final climb, but I also had committed by agreeing to go back to work within a couple of days of my arrival on Springer. Sure, it’s one of the easiest sections of the trail, but that only meant it was bound to be even more of a whirlwind tour than Maine was: there were fewer views, fewer hard climbs and fewer reasons to stop or slow down in general. It’ll be a wonder if I can even remember half of it. I’ve certainly forgotten all the names.

It all started in the dark. I don’t mean I got up before dawn. I didn’t. I mean there was no light inside. Despite being a mile from an immense hydroelectric dam, power outages are a recurring problem, and I just happened to start my hike during one of them. As a result, it did no good to make it to the lobby before breakfast ended: how breakfast was canceled. They offered me a room temperature pastry instead. Welp. Good thing we had sandwich fixings in the room. Not a particularly auspicious way to start a 22 mile hike, but on the bright side, it gave me little reason to stick around. Next was the obligatory missing a turn driving down to the dam. We ended up on the road up to the station at the base of the dam. Obviously not a place you can go without a permit, but it was interesting seeing from below the dam I’d started my hike by crossing. We turned around in the road and went all the way back around to the top. And then it was yet again time for the mandatory photo shoot, which greatly resembled the photos that started my hike, but with more orange.

Mama was so used to having me around every night again, she stalled every moment she could before letting me get away, even just for a week. Of course, she couldn’t follow, because she’d stepped in a hole and walking wasn’t working for her. Well, I stopped at the Fontana Shelter so I could look at the logs and see if I recognized anyone I’d met further north, and get an idea of what they’d been saying when they were there. The log was in a box and in multiple notebooks and pieces. It was a mess. But nonetheless, I managed to find several people I’d known, such as Limey and Damselfly.

About this time, the urge hurt me, and Copper and I went across the trail to the bathhouse. The “Fontana Hilton” is famous for being adjacent to a bathhouse with a shower downstairs. Full flush plumbing and everything. I let Copper inside to wait in there with me, not trusting him to stick around if I left him outside. At some point, while I was in there, a janitor came in to inspect the place and give it a once over, but he didn’t stay long when he saw my pack and Copper lying there. He didn’t say anything about it either. I saw his truck parked down by the shelter when I came out, so he may have been cleaning up the shelter? He drove off before I could ask. For my part, I’d forgotten to fill up on water before I left, so I fished out my water bag and took it back to the bathhouse to fill up. Once that was done, I was good to go.

I followed the trail down to the edge of Fontana Lake, where it curved around, looking fresh and cleared of leaves (which, I should add, were only just starting to turn in the South, despite being completely off and on the ground already in Maine—I seem to recall someone saying it snowed the week after I left Maine). It turned up a hill, crossed the highway, and started climbing up the hill. It was all uphill for three miles, and it was a breeze, really. The trail was broad and smooth and dirt-covered, cleared of roots, and the incline was constant and gradual. Climbing perpendicular to the slope of the hill was a welcome change from Maine’s “let’s just go straight up it!”

By 11am, I was already at Cable Gap Shelter, 7 miles in. So less than a third of the distance to where I needed to be that night. So, perfect time to take a break, right? Copper thought so. I stopped to read the logs again, and found more from Limey and one from Dangerpants, and several more going all the way back to when I was starting. All the entries had a theme in common: everyone was complaining about the difficulty of some part of the trail. My knees were shot, but I still had to laugh. Despite the North Carolina sections having some of the highest peaks elevation-wise on the whole trail, the trail between them was beautiful, graceful, flowing, forgiving. There were only a few places where I was forced to notice my knees. I remembered struggling to make it up the very same sort of slopes my first weeks out of the gate, and wondered what those guys would say if they had come back and rehiked those sections, then read what they wrote about them the first time. It’s an astounding difference perspective makes.

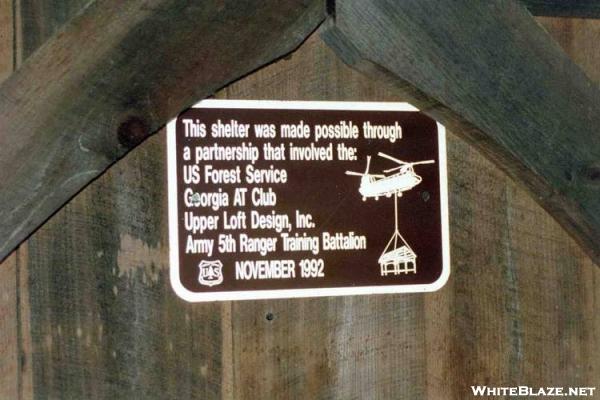

At some point, some other dude came up and wanted to talk. I think it was a couple miles past Cable Gap. There’s nothing really interesting about the trail between Cable Gap and Brown Fork Gap, so I slowed down to chat a while. It was his first time doing long-distance hiking, on a longer section of the BMT, and he was eager to get advice from a veteran. For my part, my attitude was a mixture of wanting to be supportive of a beginner, but vaguely annoyed that he always had yet another thing to say and I was forced to slow down on the one day I had the most miles to get in, but also somewhat grateful for the company. I eventually excused myself and started hiking my normal speed, putting distance between us, but I stopped long enough for a snack at Brown Fork Gap Shelter that he caught up. I had to stop there, both because it was actually lunch time, and because I was so floored to see a Maine-style lean-to my first day out in the South. I think it’s the only one in the entire Southern section.

So we sat in the shelter together, sharing snacks. He had some kind of fancy trail mix that was actually pretty good, and I may have eaten more of it than he did. I felt no guilt. I needed the calories more, and he needed to carry the weight less.

Eventually, I hiked up over the little unnamed ridge adjacent to the shelter. On the end of the ridge was a long quick drop down to Sweetwater Gap. The Brown Fork Gap Shelter contained a number of “thank God it’s over” sort of comments about it, including one from Limey, who had struck me as a fast, fit hiker when I met him in Connecticut. I tried to imagine it from their perspective: a 500 foot climb in around a quarter mile. It wasn’t hard to imagine the perceived difficulty, as I soon met a man who’d pitched a small tent right next to the trail just a few hundred feet down the hill and was collecting twigs for a small fire. I asked him if he realized there was a shelter just on the other end of the ridge, a mile away. He said he’d just parked in Sweetwater Gap an hour before and walked into the woods to start a short overnighter. He’d gotten so tired of climbing the hill, he thought it might never end, and gave up. He’d have reached the top in less than five minutes at a slow stroll. Don’t get me wrong here. I understand the virtue of quitting early when you realize you might not be cut out for the task you’ve laid for yourself, but climbing a hill? Hills are things that end! You can only climb for so long before you run out of land!

It turned out that this guy had been looking to hike in a completely different place, couldn’t find it, and ended up just getting someone to point out to him the direction to a good place to hike. He had zero knowledge of where he was going. After those few words, I moved on. He wasn’t on a timeline, so he could stop and pitch a tent at four in the afternoon. I still had eight miles to go. In the time I’d stopped to talk, Copper had laid down in the middle of his camp. Apparently, he thought that 14 miles was a long enough walk. But when I turned to leave, he grudgingly got up to follow.

The overnight stay in the proximity of an internet connection at Fontana Lodge had given me the chance to download a couple of audiobooks onto my found mp3 player. I had started “The Cat Who Walks Through Walls” when I first set out that morning, and I was finally starting to get into it, though it still seemed a lot more like Dickesque murder mystery in space than the wacky off-the-wall acid trip that it becomes by the end.

I spent the next couple of hours walking over low hills and through parking lots, undistracted and without meeting anyone else, until the sun started setting. Copper was dragging. It was time for him to eat. And I was in need of a bite myself. I sat on a log in Simp Gap, and we both ate. I put together a sandwich with bread and cheese and pepperoni, while Copper ate a double helping of his kibble. I packed up and hiked another mile, to the beginning of the Cheoah Bald climb in Locust Cove Gap. The sun was sitting on the horizon, so I was getting my headlamp out for the night-hike over Cheoah Bald when another guy came barreling up the trail from the north. He had the hardened look of a thru-hiker, so I decided to give chase.

I stayed pretty much right on his tail for the first mile or so, until it started getting twisty and rooty near the top. We talked a little along the way, as much as we could while climbing a mountain at top speed. I learned that my suspicions were correct: he’d come all the way from Katahdin, and, in fact, was hiking with a friend, who was a mile or so behind. At the summit of Cheoah Bald, I stopped a moment to take in the view of the city lights below, though it was too dark to get anything but the lights. There weren’t that many, but there aren’t many features in that part of North Carolina.

I couldn’t stay long, because there was a wind blowing across the top of that mountain that was cutting right through my fleece, and I needed to get down in some trees and moving quickly as soon as possible. I wondered if that kid I’d met earlier who said he wanted to spend the night on the Cheoah summit was crazy enough to go through with it. I certainly hoped he would pull through if he decided to pull such a stunt. It was ridiculously cold that night. I hiked the last mile down to the Sassafras Gap Shelter, getting there three or four minutes after the beast I’d tried to chase up the hill. (Wish I could remember his name!)

As soon as I stopped, I froze. I had to get in my sleeping bag almost immediately. Checking the weather near there for that night shows that it must have been below freezing that night at that elevation, and that fits my experience. I cooked a hot meal inside my bag, and tucked Copper under my legs on my pad to keep him warm. The other two southbounders (for the girl he was hiking with, whose name I also don’t recall, arrived fifteen minutes after me) were bundled up just as deep in jackets, mittens, and beanie hats, but all of us had put in well over twenty mile days, so none of us, especially Copper, had any issue getting to sleep.

Nor did we wait to get up in the morning, despite the lingering cold. It was an auspicious day, because it was the day we’d get to hike through the Nantahala Outdoor Center!!!!

When I got up to make breakfast (which was only possible because I’d known to keep my waterbag in my sleeping bag with me—I tried doing the same with my boots, but they were too big and bulky to fit at my feet), I tucked Copper into my sleeping bag and zipped him all the way up. He’s the only one who didn’t mind the smell, and it sure beat his freezing and shivering while I was away at the privy.

I was the last to leave, and the only one not planning a 30 mile day. After a mile of hiking, the downhill trek along the face of the ridgeline from the top to the NOC began, running for the next 5.5 miles, dropping 3000 feet in the process. Again, I could see how it was a climb dreaded by northbounders, but had no particular trouble with it myself. Copper found it even easier, though he couldn’t quite keep up with my springing down the hill. At Wright Gap, I came through a parking lot with a pickup trick, the bed full of animal crates, and every crate containing a noisy beagle. I had no idea what was going on, but they looked like hunting dogs, so I wondered if they might be chasing rabbits or something. I kept Copper wide of them even as I gave them a good morning. I learned not much later that they weren’t after anything so tame as rabbits. I wouldn’t have guessed their quarry myself, even if it is an obvious game in retrospect.

Soon, we crossed a road, arriving in the NOC facility. There were a number of restaurants around (many closed), but the most interesting feature for Copper was the river itself. After getting stopped by several people wanting to pet him, we managed to navigate ourselves to the water’s edge for him to get a drink. Then, I went into the bathhouse with a towel, leaving Copper tied to my pack and a picnic table, and got myself a shower. Why not? It only costs a few quarters, and even a single 22 mile day can leave a thru-hiker smelling like a bag of rotting potatoes. I figured it would be a nice thing to do for the proprietors of the restaurant just across the river, where I intended to eat my lunch. And that’s exactly what I did next. Keeping Copper tied up with my pack under a tree, I went to the restaurant and got a beer and one of their special burger designs. My phone charged at the waiter station or in the bathroom while I ate. I wanted another beer, but I decided against it, on the basis of walking another twelve miles that afternoon. I also got a bunless patty for Copper to-go, which he wolfed down with relish great exuberance.

After that, it was over the bridge, pushing through the tourist horde to get on our way. I found the two I’d spent the night with hanging out around the sporting goods store and souvenir store by the road. I didn’t expect that. I fully anticipated their being well ahead of me, but it turned out the center just happened to have some replacements for some items they desperately needed, so they’d spent shopping all the time I’d spent eating.

After establishing this, I herded Copper quickly across the busy road and we re-entered the wilderness. Just a mile in, we arrived at the Rufus Morgan Shelter, a tilty thing at the top of a leaf-strewn hill, with a weird sky blue guard-stations-shaped privy down below. We stopped inside to check out the log, but there wasn’t one that I recall. So I just chilled for a moment eating some snacks. Soon, the southbounder guy came speeding by, whistling a made-up tune loud enough to wake the dead. He didn’t even look up toward the shelter or notice I was watching. That was the last time I saw him.

Probably the main reason I stopped at the shelter after only a mile of hiking was that I was procrastinating the remaining 3 miles of climb out of the gorge. It’s not like it was difficult climbing 1800 more feet spread out over 3 miles, it’s just that the profile map made it look a lot like work, and a beer in the bloodstream made me a lot less able to resist ideas about putting off work. But once I started it, I was able to go pretty much the whole way without stopping, though I was keeping track of home many plateaus I hit, counting down the miles to the Jumpoff. The Jumpoff is a place where the trail comes right up to the edge of a cliff in order to do a switchback. The view was fairly clear from it, but it wasn’t really a view of anything. So, I didn’t bother with a picture. The climb ended a scant quarter mile later, and it was just a bit over a mile later over some short little hillocks to Wesser Bald Shelter. I stopped briefly to check it out, though my plan was really was just to drop my pack there while I led Copper down to the water source so he could get a good “I just climbed 2300 vertical feet in the last three hours” reward drink in his preferred fashion.

As soon as he drank his fill, I loaded up and kept on going up to the summit of Wesser Bald. Wesser Bald is naturally clear at the top, where a rippled slab of rock is exposed to the sun and rain. On top of that rock is built a lookout tower that is quite tall as they go.

What I remember most (aside from seeing Rambles’ signature graffito for the first time in a couple of months) about this lookout tower was the twenty dollar bill that someone had fixed quite securely to the underside of the platform, dead center, well out of reach of any but the best climber. Or maybe there was no bill there, only a graffito, and I was just dreaming about pulling such a stunt myself. But dreams and memories are one and the same, so if I imagined it, at least you can now imagine it too.

The sun was telling me I better get moving if I really planned to hike another five miles that night. I suppose it is strange from another perspective to hike at night, sometimes until the wee hours, but given that my first day’s hike on this journey ended well into the night, and I’d done the a hundred times since then, I had no concept of “hiker midnight” at all. Day or night, rain or shine, it’s always hiking weather. The next five miles were actually pretty easy. A 1.5 mile descent of Wesser Bald to Tellico Gap, across the street, then 1.5 mile ascent of Rocky Bald.

It’s kind of funny how the terrain is on this part of the trail, what with topping 5000 feet in elevation everyday while hardly breaking a sweat. (Remember, all the hiking I did on my fourth, fifth, and sixth days on the trail back in March was above 5000 feet, as there’s a 34 mile stretch at that height in the Smokeys.) In Maine, I had to work to get up above 3000 feet, and that was well above treeline. I topped 5000 feet exactly twice in all of the two months I was in New England, and since leaving it, I’d done as much in two days, with Cheoah and Rocky Balds. And in both cases, it was just after sunset I reached the top.

Headlight out, fleece on, it was a two mile walk on a tall tree-covered ridge to the shelter. Those two miles seemed like a lot more than two miles in the dark. After what felt like an hour, I passed a signpost in a gap coming off of Copper Ridge Bald (look closely, this is the only place in this entire blog you’ll see that word in reference to anything but a dog) and figured I must have reached the spot. I walked past it for a few hundred yards and didn’t find the shelter, so I figured it must have been before it or around it. I backed up and searched all around the area. I found plenty of stealth campsites at the top of the ridge, but no shelter. Eventually, I gave up and turned on my phone to consult the GPS. It said I wasn’t there yet. Those two miles were easily four miles long. Finally, I found the Cold Spring Shelter. It was impossible to miss. It was just inches off the trail, and just feet away from the effluence which lends it its name. But it was tiny, crappy, dirty little shelter, just inches off the ground and surrounded by trash and overrun by graffiti.

You’d think I would have stopped noticing graffiti, but they’re actually not that bad in Maine, largely limited to tiny autographs drawn in Sharpie. In New Hampshire, graffiti were regularly sanded off and painted over. But here in North Carolina, the picnic tables were so thoroughly carved it was hard to find a level surface to set a stove on. Actually, Cold Spring had something less than a picnic table. Some kind of weird adaptation of chairs and planks that I can’t even describe or find a picture of. But that’s beside the point.

It was dark and it was nearly as cold as the previous night. None of that warmth of the valley for Copper and me. In fact, we were 500 feet higher than we had been the previous night at Sassafras Gap Shelter. And there were no other humans to harvest warmth from (by huddling or cuddling or stealing their clothes); we had the place to ourselves. The southbounders were at least as far ahead as the next shelter up, and would probably be in Georgia in less than two days’ time. I had no good reason to go that fast, and in fact, excellent reason not to. Copper wouldn’t go that fast even if I mixed 5 Hour Energy and a bag of granulated sugar into his dinner.

Anyway, it was yet another night to race to get the bed set up before I froze, for cooking while inside my sleeping bag, for tucking Copper under my legs, and for waking up throughout the night to the dawn-bright moon and the scurrying of mice in the shelter and larger animals just outside.

In the morning, it was still pretty cold. Okay, it was really cold. I really, really did not want to leave my bag. Even lying board-straight on the stiff shelter floor seemed more appealing than getting up to go collect ice water from that little spring with my bare hands. But you can’t fight biology, and after a good long while spent staring up at the ceiling, I pulled on my gloves and went out to brave the cold. Copper seemed rather reluctant to face the day as well, so I zipped him up in my sleeping bag while I packed up, ate breakfast, and did lots of shivering. I packed up my bed last thing while Copper ate his breakfast. Finally, we started the slow, easy descent down to the road at Burningtown Gap. Although it’s normally quite nice to start the day with such a restful stroll, this particular morning it just meant it took longer than necessary to warm up.

We crossed the road a few minutes later, and maybe an hour later, we arrived at Wayah Bald Shelter. I stopped here to take Copper down to the spring for a drink, but I ended up sitting in the shelter for an hour. It’s such a nice new shelter. In fact, back in 2010, it was rebuilt, clean and graffiti-free. Of course, it’s dirty and vandalized now, but it’s still a nice design.

Yes, you heard me right. I said I stayed here for an hour for no good reason, despite the fact that I had to make 11 more miles before dark. There was stuff in there to check out, and I was enjoying sitting and being off my feet and not climbing another 600 feet up to Wayah Bald. And I think I wasn’t alone either. I think I went to use the privy, and some other guy, a section hiker, was there when I returned, and we talked a while, yet another excuse to stay. Which is probably why when I finally got the guilt drive up to speed and got moving to the top of Wayah Bald, the place had already been mobbed.

Wayah is one of those balds that never had any good reason to be a bald, and so it’s manually kept clear these days by park rangers clear-cutting it each year. It’s easily reached by car, as it’s a very short paved hike from the parking lot to the summit. And sure enough, the place was just as crowded as you’d expect such a place to be early on a Saturday afternoon. As usual the tourists all wanted to hear about the thru-hike, and wanted to congratulate me despite the fact that I was still a week from having done it. (Well, I suppose they wouldn’t ever get the chance to do so afterward, being strangers and all.) Some of them (men) wanted to tell me about their own plans for hiking the A.T. or show off their knowledge of stuff on the A.T. More often, they wanted to know about Copper, whom I allowed to just hang around the base of the lookout tower and mingle with the people there. Of course I had to put a coat on despite the clear sunny day, on account of the chill wind that’s always hanging around the bald summits in the non-summer seasons.

I told the tourists I planned on hiking into Franklin before dark, so we needed to leave pretty much immediately, no time to chat. It was 1:15pm and I still had 10 miles to go. Thankfully, the sun was setting nearly an hour later in the South than it had been in Maine, so there was enough time.

I got my audio book going and started walking, and Copper followed. I couldn’t tell you what the trail looked like for the next 10 miles, really. I remember seeing another truck with dog cages parked in Wayah Gap, but they were empty. Except for brief pauses at springs for Copper to get a drink, we didn’t stop walking until we encountered an older lady hiker headed north just north of Winding Stair Gap.

She was actually a long section hiker, and had already done quite a bit of the trail, including the section we were on. I think she went by the moniker Groovy, and she matched it with some tie-dye and peace sign accoutrements. We talked about about the extra stuff we were carrying and random other small talk. When I mentioned I’d used up a good bit of the duct tape on my poles, she gave me what she had, a long piece of tie-dye-colored duct tape. Said tape made it with me to the end of my hike. I probably still have it on those poles.

Soon after Groovy parted ways with us, we passed a guy setting up a stealth campsite just between the Forest Service Road and the highway, and I saw him as soon as I came around the ridge, because of the smoke from the fire he was getting started. I stopped a moment to talk to him while I was waiting on Copper to finish drinking out of the stream we had to walk through, but we didn’t have much to say. I really wasn’t appreciating the fact that he was stealthing so close to the water or the road, so I probably wasn’t in much of a mood to be friendly.

Copper and I found a spot along the edge of the road to give oncoming traffic a chance to see us before they got too close, and I started thumbing down a ride. It took much less time than the last time, and a older gent in a pickup truck pulled over. I lifted Copper into the bed and dropped my pack and sticks next to him, then climbed up into the cab. He told me he would be going as far the outskirts of Franklin and I said that was fine. He pulled into a convenience station of some sort and said this was as close as he was getting, and he had no idea where I was headed. Neither did I, since I had no idea of where I was on the map. (Where I was was actually off the edge of the map I had.)

I went into the convenience store, and got the impression the proprietor was very familiar with hikers. He knew exactly how to get to Haven’s Budget Inn, which has a reputation among hikers: everyone says it’s a cool place to hang out with hikers and the owners were nice, but that it’s really worn-out and grubby and unfit for human presence. After seven months on the trail, so was I. So I’d had my parents drop my resupply box there on their way back home.

The sun was still shining as I walked down the main avenue toward Haven’s, and I took careful note of the Mi Casa Mexican Restaurant as I passed it. It had been at least four months since I’d seen a proper Tex-Mex joint like that, with “Authentic Mexican Cuisine” and all the discount margaritas you can drink. I knew that’d be where I’d be unwinding that night.

I arrived at Haven’s Budget Inn after a mile of walking on sidewalks, past the neon service stations and strip clubs and casinos and banks and other hotels and historic landmarks all in a row. (Franklin is a rather strange town, I think.) It was a long strip motel like I’d come to know so intimately since beginning my hike, and it was clear it had no relationship whatsoever with BudgetInn Holdings, LLC. Ron Haven had simply named the place very aptly. There was a building across from the rooms with a porch and a family or something hanging out outside it with some small children and some large toys. Through the door on the porch was the tiny lobby. I took off my pack, tied Copper to it, and went inside.

First, I mentioned that there was a package waiting there for me, then paid nearly nothing for a room for myself and Copper. The old lady at the desk asked what kind of dog and how big, and how much he sheds. Copper, of course, sheds incessantly, but I promised he would hardly move once he was inside, and given that he’d just walked 17 miles, I was telling the truth. So, she charged me the “small dog” rate rather than the “large dog” rate and gave me a key.

I dropped my bag inside and immediately set about unpacking and getting Copper his dinner and myself a shower and a change of clothes, when I got a knock on the door. I had been intending to go back and grab the box I’d left in the office in a few minutes, but the nice lady at the counter decided to bring it out to me. I’d had to jump hurriedly back into my pants to receive it. But finally, I got everything settled and hurried through a shower so that I could make it up to Mi Casa before it got too dark.

The sun was gone when I set out in my camp shoes and clean clothes to walk the most-of-a-mile back to Mi Casa, but there was enough twilight lingering that the trees still looked green. I stopped at a gas station on the way to get some change for the washer and dryer in the motel’s laundry room when I returned, then continued on. By the time I arrived, even that light had disappeared and I was walking by the light of the signs and street lights, which were numerous enough, but not nearly as pervasive as they are in the larger cities I’ve grown up in. It was kind of a halfway sort of light between the true darkness of Maine and the utter absence of dark of Atlanta. For some reason, it seemed to me to be most reminiscent of the trail towns in Pennsylvania.

Anyway, I got myself a table at Mi Casa near an outlet so I could use my phone while I ate delicious Mexican cuisine and drank a margarita or two. I stayed just over an hour, paid, and walked back to make sure Copper didn’t need more water or a trip outside and get my laundry washed and dried before the people who lived in the apartment above the laundry room went to bed (by request of the lady at the desk). Copper seemed perfectly content to lie in one spot just as I’d promised, so I started my laundry, then lay down spreadeagled in the middle of the bed and put the TV on. I decided to save my food-packing job for the morning, as I had no particularly ambitious plans for the next day’s hike. As soon as I finished the load of laundry I went to sleep.

In the morning, I made my usual morning hiking mix for breakfast, as the motel had no breakfast offerings and I didn’t feel like wasting time going out to look for a restaurant. I had a lot of food to pack.

I packed enough food for Copper and myself to both make it to Hiawassee in four-and-a-half days, and this took process took right up until the time I was supposed to be checked out. I dumped a pile of garbage in the motel’s dumpster, and left the remaining contents of my food box for any other southbounders that might come through. The lady said they didn’t really keep a hiker box past April, as they didn’t see thru-hikers for most of the year, even in the winter. As I understand it, there’re about a hundredth as many Southbounders as Northbounders coming through Franklin each year. So, I said they could keep whatever of it they wanted and toss the rest.

Copper and I walked out to US64 to get a ride out to the trail. It’s not the safest place to stand in the middle of the day, but I figured I’d be more likely to find someone going my way on the highway than in town. I had an ulterior motive too. I wanted to get some pictures of Franklin’s most historical site in the daytime:

This hill is reckoned to have been built by peoples of the Mississippian cultures in around 1000 CE. It marks the center of, and is all that remains of, an early Cherokee town, called Nikwasi, that stood where Franklin is today. In some ways, one might consider it the capital of the Cherokee nation because of what transpired there when the European colonists arrived. The people here had long been peaceful farmers in a pretty much egalitarian society with a very distributed and democratic government. Or, to put it more simply, they weren’t very good warriors.

This hill is reckoned to have been built by peoples of the Mississippian cultures in around 1000 CE. It marks the center of, and is all that remains of, an early Cherokee town, called Nikwasi, that stood where Franklin is today. In some ways, one might consider it the capital of the Cherokee nation because of what transpired there when the European colonists arrived. The people here had long been peaceful farmers in a pretty much egalitarian society with a very distributed and democratic government. Or, to put it more simply, they weren’t very good warriors.

English colonist Alexander Cuming called a meeting of all the Cherokee tribes and villages in this place. Thousands of Cherokee attended. His goal was to have them select a handful of representatives from their leaders, seven men in all, one of whom (Moytoy of Tellico) would be chosen as “Emperor” of the Cherokee, or the single point of contact between England and the Cherokee nation. All seven would accompany him to England. Moytoy (whose name was a European mispronunciation of Amo-adawehi, meaning rain-maker) was crowned with the “Crown of Tannassy (Tennessee)” right on top of this mound, where stood a longhouse, and, for thousands of years before that, a ceremonial platform. The interesting part of all this is that Cherokee town councils usually were usually comprised of a roughly equal number of men and women. The only reason only men were selected here is that Cuming insisted upon it.

Not long after that, during the Seven Years’ War, fearing the people of Nikwasi and its surrounds were allied with the French, destroyed the towns and villages here. The Cherokee rebuilt, then ceded their lands to North Carolina in treaties of 1817 and 1819. The town of Franklin was founded, and, as you can see, buildings and roads were built over the remains of the Cherokee village, but no one had the guts to build over the millennium-old mound. I would say it had something to do with the legend about the horde of Nunnehi that once sprang forth from the mound to save the Cherokee villagers from a Creek onslaught, but some cynical part of me sees how closely around it the various businesses have encroached and says the mound would have been bulldozed a generation ago if it weren’t on the National Register of Historic Places.

Copper and I weren’t the only ones out on the highway hitchhiking that day, but the other guy definitely wasn’t a hiker. He was sitting on a suitcase with a pile of things next to him. He didn’t seem to be trying very hard to get attention, and I figured I had a much better chance of getting a ride if I were far up the road past him so that a) potential drivers would be primed for seeing hitchhikers by the time the saw me and b) they could pick Copper and me up without feeling bad about not picking him up also. Once we got down past the next traffic light, it wasn’t that long before a married couple in an SUV took a chance on me. It turned out they hadn’t planned on going as far out as we were, but they went out of their way to get me back to Winding Stair Gap, which turned out to be much farther than I remembered on my ride in. They left me in the parking lot around 1pm, and I immediately started up the hill.

It was an easy three miles over the hill to Rock Gap, where I stopped in the Rock Gap Shelter to fix and eat my lunch. I remember this shelter pretty well, because it’s the only one I can remember having a porch extending out of the side, so that there was a wall between the picnic table and the sleeping area. On this wall was a bulletin board full of drawings and scribblings of local elementary schoolers depicting and documenting facts about black bears. On the table was most of a deck of playing cards, so I played around with those while I ate, as it had been quite a while since I’d handled a deck.

I probably stayed there a bit too long, since, judging by the clock, I couldn’t really waste anymore time that day. It was 3.5 miles from there to Long Branch Shelter, where I remember seeing some older hikers already settling in for the evening. One was already in his sleeping bag. I stopped in to say “hi,” eat some snacks, and see what everything looked like, and chat for a few minutes while Copper took a break, but I could see the sun setting and, despite those guy’s expectations, I had to do another eight miles before I slept.

I definitely remember there being people up on top of the mountain, though. Tourists, since it was Sunday evening and it’s possible to drive to within a few minutes of the summit. It was late, though, the sun was below the horizon and it wasn’t even visible through the fog. Twenty feet down the slope was nothing but white. I climbed the fire tower anyway, just because it was there. The couple who I met there said I’d missed a wonderful sunset.

The couple wondered a bit at my decision to put in another six miles after dark, but seemed far more comfortable with the concept than other tourists. I got the sense they’d done quite a bit of hiking in their lives. The descent of the steep rocky side of Albert Mountain after dark was about the trickiest thing I did in all of the South. For some reason, I never saw any complaints about it in the logs, but I wouldn’t be surprised if someone told me it’s the most difficult section of trail in North Carolina. Fortunately, it lasts only a tenth of a mile, and soon I was walking a smoother slowly descending trail. Moments later, a car came by painting the trees in its headlights, illustrating how the road was just a few years from the trail on this ridge. It was the couple from the top headed home.

The next six miles were actually pretty easy, and I wasn’t super exhausted from a long day of hiking. In fact, I had spent a great deal of the time since I returned to the trail just sitting still. As a result, we powered into the vicinity of the Carter Gap Shelters just a couple of hours later. I selected the newer, larger, fancier one, and sat down to cook my supper. (Copper had already eaten his while I was climbing the fire tower.) We had the place to ourselves again, and, with the weather warming up slightly, had a pleasant night’s sleep.

Finally, the day came in which I would be returning to my home state for the first time in over 7 months. I didn’t waste too much time getting up and getting out once I woke up in the morning, since I had a twenty mile day planned. I hoped Copper could handle it, since this was record mileage for any given week of the trail for both of us. He’d done more miles in a day, sure, but he’d always had a break soon after. This was the fifth day of our Southern hike and we’d done 72 miles in the first four days (22 miles, 18 miles, 16 miles, 16 miles), and now a twenty to top it off. Fortunately, the whole reason for this longer day was that I had planned to meet Mama at Dick’s Creek Gap early the next day for some basic resupply, and if Copper wasn’t up to finishing with me, he would have the opportunity to get off the trail there.

The trail was easy on us, staying pretty smooth and near level for the first three miles, then taking a long, slow three mile climb 1000 feet to the top of Standing Indian Mountain. At 5,498 feet, Standing Indian is the highest peak on the A.T. south of the Smokeys. Once again you can see the North/South contrast here, as Standing Indian is a couple hundred feet taller than Katahdin, but this is what it looks like at the summit:

Look how lush and green it is! Of course, when I saw it, most of the leaves were starting to turn red and orange and the view was hazy, but the contrast with the summit of Katahdin was still readily apparent. Latitude makes such a difference. (Wikipedia and a little guesswork says that proper treeline would start between 7,000 and 9,000 feet at these latitudes, but there are no mountains that high in the Appalachian range, so we can’t know for sure.)

Coming down the other side of Standing Indian was ever so slightly steeper, but not steep enough to be a pain in the knees. I passed a couple of guys near the bottom of the climb heading up, and wished them luck and better views than I’d seen. They weren’t in the greatest shape, so I have to wonder whether my opinion that the climb was easy would end up seeming like a lie to them. I tried to qualify some, but it would have been hard to tell them it would be difficult without feeling like a liar, even if they might have found it so.

There were even more weekend hikers hanging out at the Standing Indian shelter halfway down the slope. I stopped and chatted with them for a few minutes, but it was still morning, so I didn’t bother to make lunch yet. Muskrat Creek was only 5 miles further on. Unfortunately, I found I needed use of the privy, and stayed longer than I meant to.

Eventually, we set out again, crossing a forest service road at another of the countless “Deep Gaps” on the trail, and climbed past the junction for a trail for the most humorously named mountain in the South: Chunky Gal. All the way I was listening to my audiobook and thinking about haunted houses and zombie hashing and such without really paying attention to too much of what was around me. The trail was so easy as to be boring. We arrived at Muskrat Creek Shelter in the middle of the afternoon and took our packs off to sit a spell and eat. We were the only ones there.

The shelter looked like most of the others in the area, with a porch extending from the front to cover a picnic table, and benches and shelves running around the perimeter of the porch. Copper ate his supper here and we stayed for a few minutes until it seemed like dusk might be heading our way. We left again, Copper wishing he didn’t have to and I myself realizing that we wouldn’t possibly reach the next shelter seven miles away until well after dark. If I weren’t on a deadline, I probably would have stayed where I was, figuring a 13 mile day was good enough given our record for the previous four days.

Two miles away, we arrived came down the wide ridge into Bly Gap. Yep, the gnarled old oak was right there where the guidebook said it would be, and I, figuring that it was such an oft-photographed tree that my dim, dusky image of it wouldn’t add much to the collection, and would certainly keep me awake a few minutes longer, passed it by without a second glance.

Just a little beyond was a campsite with a couple of weekenders setting up tents and mostly ignoring me. Their dog had something to say to Copper, but Copper wasn’t paying attention, being too busy trotting down the hill after me. The ridge wanted to soar back up to the elevation we’d come from, and, in fact, maintains that sort of elevation almost all the way to Hiawassee. The A.T., however, took a hard left down the side of the ridge, heading well down for a lower ridge, to rarely and barely ever ascend above 4000 feet for the remainder of the distance to Amicalola. Just a hundred yards down this hill, we came to a sign nailed to a tree, indicating that I had finally come back home to Georgia.

Less than a mile later, near Rich Cove Gap, I came across a man in camo fatigues with a dog. Of course, we had to stop so Copper could offer salutations in the dogly way. Turns out the guy was out hunting hogs, and had walked into Georgia, where his dogs had given chase, in order to gather them up and take them back to North Carolina, where hunting hogs with dogs was actually legal at that time. He showed me the GPS equipment he was using to track the other two dogs, explaining that the dog with him was older and hadn’t been able to keep up with them. It was rather fancy stuff, and my first encounter with high-tech hunting. Well, at least I wasn’t as clueless about the trucks with dog cages I’d been seeing parked along the trail. He also explained his method for hunting, which he claimed involved putting himself in the path of the dogs and ordering them to harry a hog and flush it toward him until he could pounce on it with a knife. Personally, I figure I’d just arrange a command for the hounds to suddenly clear out so I could safely down the hog with a barrel full of buck shot at a distance. Perhaps he’s the sort whose idea of a rodeo is footrace against a herd of angry bulls in the streets of Pamplona. But it was certainly an enlightening chat, and as it passed, the last of the light disappeared, while Copper took a nap at my feet. Eventually, I pulled out my headlamp and said I had to be going. I put my audiobook back on to tune out the night and marched brightly on.

Around a mile later, as we started descending even further toward Blue Ridge Gap, a saw and heard a torrent of shadows fly across the trail just five yards further up the trail. I froze in terror. I snatched my earphones out and listened, and the scratching and snorting of more than a few hogs was clearly audible in the forest to the right side of the trail. I was worried I’d have to face a full-sized hog in full panic, and knew I couldn’t possibly take it on. But even more than that, I was worried that Copper would smell them and chase them down the way he had the skunk in New Jersey. I knew he didn’t stand a chance against a hog by himself if he backed them into a corner, and would likely be mauled. I decided to handle it the same way I handled the porcupines: I’d grab his handle and hold onto him until we got safely past to make sure he wouldn’t bolt after them. I turned around to tell him to stay put, but he was gone.

Had he already given chase? He was nowhere within the range of my high spotlight from the trail nor did I hear him move when I called. Which way had he gone? Was he sneaking up on the hogs? Was I about to hear a fight? Had they already bulldozed him to the ground? How far off trail would I have to go to find him, or worse, his corpse? Had he seriously walked all the way from North Carolina to New Hampshire with no major injuries only be taken out now within a few days of the finish?

What felt like several minutes later, I heard some rustling going on down the hill on the left side of the trail, and soon Copper came trundling back into the light, looking invigorated and none the worse for wear. I think he did smell the hogs, but he caught their backtrail, and had headed down toward the creek where they had come from, thereby managing to avoid any real encounter with them. He and I both got really lucky there.

We started walking again, and soon my heart settled back down into my chest. I put the audiobook back on, and we arrived in Blue Ridge Gap moments later. Here, I decided to sit down and eat a snack and see how much further I had before I got to the shelter. Which is to say, I was stalling on the last climb of the night (and the first climb after a long five mile descent). The map said I just had a half-mile 400-ft. climb to the top of a miserable wooded bump called As Knob, followed by a half mile mile 400-ft. descent to the shelter. Well, the sooner I started, the sooner I could eat and get to bed.

This was another one of those sections of trail I vividly bright little images of even after all this time, and how I generally felt during it (and mostly how much I wished I were done and in the shelter already), but there’s not enough detail to put into words. I remember moving as quickly as I could to resist the urge to stop. I was struck by how brightly lit certain sections of the trail seemed to be, coated with some kind of sand or soil with a high albedo, and how much curving the trail did, managing to go from Blue Ridge Gap to Plumorchard Gap by completely circling As Knob and utterly avoiding its summit. I was really turned around by the time I came down the ridge into the gap, and knew not which way I was headed.

When I hopped over some roots to land at the intersection with the side trail to Plumorchard Gap trail, I was a solid five minutes ahead of Copper. He just couldn’t keep up. I stood there that long to make sure he got close enough to see me turning off the trail, in case he neglected to follow my odor. A quarter mile later, we pulled up under an enormous shelter. I was hoping we’d have the place to ourselves so that I wouldn’t be waking anyone up, but I had nothing to worry about. It was absolutely enormous and absolutely abandoned.

Although it had a second floor way up in the roof, I slept right in the middle of the bottom floor, because otherwise, how would I keep Copper warm? It fell quite cavernous in the middle of the shelter designed to accommodate 14, but I had no trouble getting to sleep.

I woke up to a lovely morning, and had no particular reason to leave with any particular speed. I had five miles to go to get to Dick’s Creek Gap to meet my mom, and she’d be arriving late morning. I had time to explore the shelter and read the log and collect water and pack up and enjoy my stroll up to Bull Gap and back down again to the lowest point on the southern portion of the trail. Dick’s Creek is really just the top of a hill along US76 where there are some picnic tables and a small parking area. I knew the place because Mama and I had done trail magic there some time previously (March 2012, I think). I didn’t see her there and Copper and I sat down to wait for her, but it turned out she was already in the area and had been there once, and soon came back to see us. I was just going to pick up my package and keep going, but I decided I might like to have a shower, so I had her drive me to Unicoi State Park, where I was able to steal a shower from the bathhouse and charge my phone. Then we went over to the conference center/hotel they have there and used their wi-fi for a bit. I had a few urgent emails to make about my arrival back in Georgia, and more importantly, I had finished my audiobook and had to download a new one. After it finished copying, I went out to start packing up all the new snacks and food I was picking up.

On the way back to the trail, we picked up some boiled peanuts as a treat. It was 4pm by the time I was ready to get back on the trail. Having seen Copper struggle to keep up for the last couple of days, and knowing I was going to have to maintain the same pace for several more days, I decided to let him go home without me. He would have time to rest and meet me again at the end of the trail.

And, with only 70 miles to go, I would be at the end of the trail in just five more days, and I wouldn’t be alone. Of course, if you were there, you’ll remember that. But that’s going to have to wait for another post, because this one is already way too long. See you back here in another couple of weeks! We’ll see this thing through yet!

I guess I’ll never tire of reading these posts and viewing the photos. I am still amazed at the discomfort you endured, the pain you worked through, and the mental strength that it took to finish this journey. #foreverimpressed

I’m still hanging in here with you … looking forward to every post! So many people think the AT is an easy hike because it is a marked trail; little do they understand the mental energy as well as the physical endurance that is required to complete the long hike. These are impressive daily miles that you logged during these last weeks! Again, thanks for sharing!

I have encountered far more people who think the AT is an extremely difficult hike, and of course, they are equally as wrong. The truth, as always, is somewhere in the middle. I have to agree with those who say that the A.T. provides challenging terrain in exchange for easily accessible resupply and plenty of company and social interaction. Hiking gets easier as time goes on, while being alone only gets harder, so the A.T. is the perfect combination.

Wow! there is so much to read through here. I like your post quite much. I love hiking, But i do believe hiking is not way easy as it looks like. I just want to congrats and give a big thumbs up to your absolutely great work.